J. Philippe Bankert, AI assisted, 17 February 2025

Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is increasingly shaping both modern warfare and peacekeeping efforts. Advanced algorithms can drive autonomous weapons and intelligence analysis on the battlefield, but the same technologies also offer powerful tools for preventing conflict and aiding diplomacy. From predicting where the next crisis might erupt to assisting negotiators in finding common ground, AI’s dual-use nature presents both opportunities and challenges for global security. A new frontier – Quantum AI (the convergence of AI with quantum computing power) – further promises to amplify these capabilities, potentially transforming conflict prediction, verification, and diplomacy at an unprecedented scale. This report examines how AI (and Quantum AI) can be leveraged to prevent war and foster peace, with deeper analysis of key applications such as conflict prediction, diplomatic assistance, misinformation mitigation, arms control verification, and integration into peacekeeping. Historical case studies illustrate how AI might have accelerated past peace processes, and we discuss emerging real-world examples of AI contributing to de-escalation. We also address the ethical and strategic implications of relying on AI in high-stakes peace and security scenarios, and highlight current initiatives by governments, international organizations, and NGOs to harness AI for diplomacy and conflict resolution.

AI-Driven Conflict Prediction and Early Warning

One of the most promising peace applications of AI is in conflict early-warning systems. AI algorithms can process vast amounts of data – from economic indicators and political events to social media and satellite imagery – to identify patterns that often precede violence (weizenbaum-institut.de). This data-driven foresight enables a shift from reactive crisis response to proactive conflict prevention. For example, machine learning models today analyze historical conflict data to flag rising tensions; in fact, rudimentary machine learning was even used during the Cold War to predict the arms race dynamics between East and West. Modern systems are far more sophisticated: the Violence & Impacts Early Warning System (ViEWS) developed by Uppsala University and PRIO uses AI to crunch dozens of variables (conflict history, political instability, economic trends, etc.) and can forecast the likelihood and intensity of conflict up to three years in advance (kluzprize.org). Such AI-powered early warnings highlight potential hotspots (e.g. regions where spikes in unrest or resource scarcity suggest a high risk of conflict) (kluzprize.org) allowing the global community to act before violence erupts (visionofhumanity.org).

AI-driven prediction isn’t limited to long-range forecasts; it also operates in real time. Geospatial AI tools integrate satellite imagery with machine learning to monitor conflict indicators on the ground, such as unusual troop movements or population displacements (weizenbaum-institut.de).

These tools can alert peacekeepers and decision-makers to imminent threats. For instance, spikes in inflammatory rhetoric on local social media or radio can be detected by AI sentiment analysis, signaling growing anger in a community. In one United Nations pilot, an NLP algorithm analyzed live radio call-in shows in Uganda to gauge community grievances – providing peacebuilders with insights into social tensions that might otherwise go unnoticed. Armed with such warnings, mediators or UN officials can deploy resources or initiate dialogue before clashes break out. Essentially, AI acts as a conflict “weather radar,” scanning the horizon for storm clouds of violence.

Scenario simulation is another facet of AI conflict prediction. Advanced models can simulate political and military trajectories to explore the likely outcomes of different actions (weizenbaum-institut.de).

Policymakers can ask “What if?” and let an AI system project how a negotiation concession, a peacekeeping intervention, or, conversely, a military strike might play out over weeks or months. These simulations provide a form of decision support: by seeing which scenarios lead to escalation versus de-escalation, leaders can make more informed, peace-promoting choices. While such simulations are not guarantees, they offer a data-informed guide that complements human expert judgment.

Current projects exemplify AI’s potential here. Beyond ViEWS, initiatives like the UN’s use of AI-enabled data hubs for horizon scanning are underway (press.un.org; unitar.org). Early successes are beginning to emerge. In some cases, AI-driven alerts have prompted timely preventive diplomacy – for example, by flagging communal tensions in a region, enabling UN mediators to organize local peace dialogues before violence sparks. As AI early warning systems mature, they could significantly improve global stability by helping actors intervene at the earliest signs of conflict, “nipping it in the bud” before full-scale crises develop.

AI Assistance in Diplomacy and Peace Negotiations

Beyond prediction, AI is proving to be a valuable assistant in the art of diplomacy and conflict resolution. International peace negotiations are incredibly complex, often involving years of talks, troves of documents, and deeply entrenched positions. AI tools can help make sense of this complexity and support human negotiators in several ways:

- Data-Driven Mediation: AI can digest large archives of past peace agreements, negotiation transcripts, and research on conflict drivers to extract insights on what approaches tend to succeed. Machine learning models have been used to analyze historical conflicts and identify which peacekeeping strategies correlated with durable peace (defenceagenda.com). This kind of analysis can inform mediators of effective strategies (for example, the importance of power-sharing or economic development programs) based on what has worked elsewhere.. Essentially, AI provides negotiators with an evidence-based playbook of peacebuilding.

- Identifying Common Ground: During talks, AI algorithms (including advanced natural language processing models) can assist in finding overlaps in parties’ positions. By processing negotiation documents and public statements, AI might highlight where opposing sides actually share objectives or where a slight reframing could turn a zero-sum issue into a win-win. Indeed, large language models today can emulate human-like dialogue; they can serve as impartial “sounding boards” – helping diplomats rephrase proposals or suggesting language that emphasizes mutual gains. Experimental AI systems have even been designed to facilitate “digital dialogue”, enabling stakeholders to deliberate via a multilingual AI platform that translates and mediates the conversation in real-time. This can amplify voices that are usually excluded (such as local community leaders who can participate through an AI-mediated channel) and ensure a peace process is more inclusive..

- Simulation of Agreements: Just as AI can simulate conflict scenarios, it can simulate negotiation outcomes. Diplomats can input key parameters of a potential peace deal, and the AI can project possible public reactions, economic impacts, or security outcomes of that deal. For example, an AI might predict that a proposed border arrangement would reduce violence by X% but might falter unless certain economic aid accompanies it. By predicting the long-term implications of agreements, AI helps negotiators tweak deal terms for better viability (defenceagenda.com)..

- Real-Time Translation and Sentiment Analysis: Miscommunication is a constant risk in international diplomacy, especially when multiple languages and cultures are involved. AI-powered translation tools now offer near-instantaneous, accurate translation between dozens of languages, which bridges linguistic gaps in meetings and correspondence (defenceagenda.com). Coupled with sentiment analysis, AI can also gauge the tone and emotional content of communications, alerting negotiators if a message may be interpreted negatively by the other side (defenceagenda.com). By catching subtle nuances and cultural cues, these tools reduce misunderstandings and build mutual trust faster.

- Virtual Reality and Training: Innovative uses of AI include combining it with virtual reality to assist diplomacy. For instance, VR simulations (enhanced by AI analytics) can immerse negotiators in the conditions of conflict zones to build empathy. AI-driven interactive role-play can train diplomats in handling tough scenarios – essentially a high-tech rehearsal for real negotiations. This preparation can lead to more effective performance at the negotiation table.

In practice, we are starting to see AI’s diplomatic support capabilities. Data-driven diplomacy platforms are under development to help mediators map out the interests of each side and even suggest compromise formulations. One real-world example is the software CogSolv, which aims for “deep conflict resolution” by processing knowledge about conflict dynamics and offering field operators decision support for just resolutions. In a trial, CogSolv was able to simulate local conflict situations and, for example, suggest focusing on “Local Dignity” rather than a generic “Human Rights” framing when engaging a community – tailoring the approach to what resonates better with participants (thesecuritydistillery.org).

Such AI guidance can decentralize expert knowledge, putting intelligent coaching tools in the hands of mediators on the ground, even if they lack extensive experience in psychology or local culture (thesecuritydistillery.org).

Looking back, one can imagine how protracted peace processes might have benefited from these tools. The Northern Ireland Good Friday Agreement (1998), which came after 700+ days of painstaking negotiations (ireland.ie), might have been reached faster if AI had been available to analyze proposals and public sentiment. An AI could have helped negotiators test the impact of various power-sharing arrangements or policing reforms and identified a formula acceptable to both Unionists and Nationalists more quickly. Similarly, in the Israeli-Palestinian negotiations, AI assistance could have been used to craft creative solutions – for instance, by sifting through thousands of possible land-swap configurations to find ones that maximize mutual benefits, or by monitoring real-time feedback from both Israeli and Palestinian populations on draft terms (via sentiment analysis on social media) to steer talks toward areas of potential public support. While AI cannot magically resolve deeply rooted conflicts, it can provide augmented intelligence to human peacemakers – illuminating solutions that might not be obvious and helping negotiators avoid pitfalls that have derailed past talks.

Combating Misinformation and Propaganda with AI

In the digital age, misinformation has become a weapon that can inflame conflicts and sabotage peace efforts. False rumors, hate speech, and “deepfake” videos can rapidly spread, eroding trust between communities or states. The stakes are high: as UN Secretary-General António Guterres warned, “deep fakes could trigger diplomatic crises, incite unrest and undermine the very foundations of societies.” Therefore, mitigating misinformation is a critical peacekeeping task – one where AI is both part of the problem and part of the solution.

On one hand, advances in AI (especially generative AI) have made it easier to create realistic fake images, videos, or news reports that adversaries might use to provoke conflict. For example, a deepfake video of a world leader announcing a (false) declaration of war could conceivably push rivals to real-world retaliation. AI-enabled propaganda bots can amplify divisive narratives on social media, creating the illusion of widespread anger or support. These malicious uses of AI threaten stability by fostering confusion and mistrust.

On the other hand, AI provides powerful tools to detect and counter misinformation. Governments and civil society are increasingly deploying AI-powered systems to fight back (cambridge.org). Some key applications include:

- Automated Fact-Checking: AI algorithms can scan news articles, images, and videos to check their authenticity. For instance, an AI might use reverse-image search and metadata analysis to flag that a viral photo of alleged “atrocities” is actually old or doctored. Natural language processing can compare claims in a social media post against reliable data sources, quickly identifying falsehoods. These AI fact-checkers operate at a scale and speed impossible for human fact-checkers alone.

- Content Moderation and Hate Speech Removal: Social media platforms employ AI systems to monitor content in real time and remove posts that violate rules (e.g. explicit incitement to violence or dehumanizing language towards a group). In conflict-prone settings, this is crucial – hate speech online has been shown to precede outbreaks of violence. AI moderation isn’t perfect (context is hard for algorithms), but it serves as a first line of defense to dampen digital sparks before they ignite real conflict.

- Disinformation Early Warning: Similar to conflict early-warning systems, there are now early-warning systems for harmful misinformation. AI can map networks of bot accounts or known propaganda sources and alert authorities when a coordinated disinformation campaign is ramping up (cambridge.org).

For example, if hundreds of new accounts start tweeting a particular rumor about an upcoming election or peace treaty, an AI system will detect the anomalous pattern and raise an alarm. This gives peacekeeping authorities a chance to respond with accurate information or cyber countermeasures swiftly.

- Deepfake Detection: Researchers are developing AI that specializes in identifying deepfakes by analyzing subtle artifacts in audio or visuals (e.g. unnatural eye blinking, inconsistent lighting, digital compression signatures). Deploying these detectors can help verify important communications. For instance, if a purported video message from a head of state surfaces during a crisis, AI vetting can quickly confirm if it’s genuine or a synthetic fake engineered to mislead.

- Counter-Messaging: AI can also help generate positive content to counteract harmful narratives. By analyzing which false stories are spreading, AI systems can assist in crafting effective counter-narratives or public information campaigns. This might include tailoring messages to specific audiences and using sentiment analysis to ensure the tone will resonate (for example, calming fears if misinformation is causing panic). In essence, AI can be used to flood the information space with truth in response to lies.

There are real-world initiatives embodying these approaches. The European Union, for example, has funded projects under its Horizon program to develop AI tools for disinformation detection and debunking, often in partnership with universities (cambridge.org).In the United States, much of the cutting-edge work on AI and misinformation comes from tech companies and academia, with support from private foundations. Grassroots organizations are also empowered by AI – there are efforts combining human expertise and AI (a “hybrid” approach) to train community members in identifying and refuting fake news circulating in their local networks. By mapping how false information propagates and who is most influential in spreading or stopping it, these projects enable targeted interventions. For instance, an AI analysis might reveal that a particular conspiracy theory is mainly confined to a few Facebook groups – allowing peacebuilders to focus their counter-messaging or dialogue efforts on those specific communities.

In conflict zones or fragile societies, controlling misinformation can literally save lives. One could consider, hypothetically, the Rwandan genocide in 1994 which was exacerbated by hate radio broadcasts; had modern AI moderation and detection been available, such inflammatory content might have been identified and jammed or countered earlier. In today’s contexts – be it rumors of electoral fraud that could spark unrest, or manipulated videos aiming to derail a peace deal – AI’s ability to rapidly dismantle false information is becoming an indispensable part of peacekeeping and diplomatic strategy. Of course, these AI systems must be used carefully, with respect for free expression and transparency, to avoid any perception that “AI propaganda” is simply countering one bias with another. When used responsibly, however, AI can significantly mitigate the weaponization of information, building a more truthful foundation on which peace efforts can proceed.

AI for Arms Control and Verification

Trust is the bedrock of any arms control agreement or ceasefire – and trust comes from verification. AI is poised to dramatically enhance the monitoring and verification of arms control treaties and peace agreements, making it easier to detect violations (or confirm compliance) in a timely, credible manner. Historically, arms control verification has relied on tools like satellites, reconnaissance aircraft, seismic sensors, and human inspectors painstakingly analyzing data (blog.prif.org). AI can supercharge these efforts by processing data faster, more comprehensively, and spotting subtle patterns humans might miss.

Key applications of AI in this domain include:

- Satellite Image Analysis: Overhead imagery is crucial for monitoring military installations, nuclear facilities, or conflict zones for changes. AI image recognition can scan thousands of satellite photos daily to identify anomalies – for example, the appearance of new structures at a missile site, unusual movement of vehicles, or heat signatures indicative of nuclear tests. An AI system can be trained on what normal activity looks like at a monitored site and then alert inspectors the moment something deviates from the norm. This continuous, automated watchfulness greatly increases the chance of catching treaty violations in real time. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and others have been actively exploring AI for these purposes (blog.prif.org) .

- Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) and Sensors: Drones and remote sensors are already used in monitoring ceasefires and weapons stockpiles. AI can enhance UAV operations by autonomously surveying border lines or demilitarized zones and detecting forbidden activity (like troop concentrations or gunfire) without endangering human peacekeepers. Notably, non-weaponized autonomous drones using AI have been employed to monitor lines of contact and flag cease-fire violations, reducing risks to observers on the ground (pragmaticcoders.com). The AI helps process the video feed in real time, distinguishing normal civilian activity from military movements. In UN missions since 2013, unarmed surveillance drones have been deployed (e.g., in the Democratic Republic of Congo), and integrating AI could allow them to not only record data but also interpret it on the fly (thesecuritydistillery.org). .

- Arms Treaty Verification: For formal arms control agreements (like those limiting nuclear weapons or missiles), AI can assist inspectors by aggregating multi-source data – satellite images, shipping records, radiation sensor outputs, open-source intelligence – to ensure parties are honoring their commitments. For example, algorithms can cross-analyze global shipping and customs data to detect clandestine arms transfers or dual-use components being smuggled in violation of sanctions (blog.prif.org). X-ray scans of cargo containers at ports can be automatically interpreted by AI to flag suspicious shapes that might indicate hidden weapons (blog.prif.org). These applications extend to export control regimes as well, catching illicit procurement networks that would otherwise slip through the cracks.

- Ceasefire Monitoring and Disarmament: In peacekeeping contexts, AI aids verification of ceasefire terms. Acoustic sensors with AI can differentiate between, say, a backfiring vehicle and a gunshot – providing clarity on whether a gunfire incident occurred. AI analysis of surveillance video can log every person or vehicle passing through a checkpoint, helping verify that armed groups are not infiltrating forbidden areas. As disarmament processes unfold (like rebels turning in weapons), AI-powered databases can keep meticulous track of weapons collected and cross-check serial numbers or types against agreed totals. According to reports, AI systems processing drone and satellite imagery have been used to observe disarmament and even identify war crimes in conflict zones (pragmaticcoders.com). By cataloguing evidence (like mass graves or use of banned munitions), AI not only enforces agreements but also holds perpetrators accountable, which in turn reinforces trust in the peace process.

The benefits of AI in verification are significant: greater transparency, faster detection of non-compliance, and reduced workload for human monitors. This can build confidence among parties – if everyone knows cheating is likely to be quickly exposed by objective AI surveillance, there is less incentive to break the rules and more incentive to sign agreements in the first place. For example, during the Cold War, U.S. and Soviet arms treaties were limited by verification capabilities; today, AI could enable far more intrusive and reliable verification, potentially making deeper arms reductions feasible. An AI that monitors a remote border via satellite 24/7 is like an unblinking eye, assuring each side that it will be alerted if the other side masses troops or moves heavy weaponry into a prohibited zone.

Of course, there are challenges. AI isn’t infallible – false positives (incorrectly flagging a treaty violation) could cause panic or accusations. Therefore, AI outputs must be carefully reviewed by human analysts to avoid misinterpretation. Additionally, parties need to agree on using such technology; sometimes countries are wary of too much monitoring, especially if AI monitoring data could be hacked or misused. And importantly, as AI and other emerging tech become central to verification, new treaties may be required: experts have suggested that just as we had treaties for nuclear inspection, we might need international agreements governing the use of AI, robotics, and even quantum sensing in arms control (cgai.ca).

Nonetheless, pilot programs show promise. The United Nations has acknowledged that AI can assist in monitoring and verifying compliance with international arms control agreements (unitar.org). The Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF) notes that while many projects are still in proof-of-concept phase, AI is making “tremendous advances” in the civilian sector that can be adapted for arms control verification. Even small successes – like an AI system that reliably analyzes satellite photos to confirm a chemical weapons facility has been dismantled – can have outsized impact on peace and security. In sum, AI stands to become a force-multiplier for arms control, enhancing the integrity of peace agreements by ensuring that “trust, but verify” is more than just a slogan, but a continuously achievable reality.

Quantum AI and Global Stability Efforts

As we look to the future, Quantum AI looms on the horizon as both a transformative opportunity and a strategic challenge for global peace and security. Quantum AI refers to AI algorithms run on quantum computers or enhanced by quantum computing capabilities. While still in early development, the combination of quantum computing’s immense processing power with advanced AI could rewrite the rules in many domains – including conflict prediction, cryptography, and diplomacy. It is important to understand how quantum AI might enhance global stability efforts, and what new risks it might pose.

On the positive side, quantum-enhanced AI could dramatically improve data analysis and modeling for peace and conflict issues. Quantum computers excel at solving complex problems with vast combinations (thanks to quantum parallelism). This means a quantum AI system could, in theory, analyze far more variables in a conflict scenario than any classical computer today. For example, modeling the global economic ripple effects of a regional war – or the intricate interdependencies of climate change, resource scarcity, and conflict – might become feasible. By crunching such enormous simulations, Quantum AI could give world leaders uniquely rich insights into the long-term consequences of their actions, potentially encouraging more prudent, peace-preserving decisions. As one analysis notes, merging quantum computing with AI “opens up many possibilities,” as quantum machines can train and run extremely complex AI models that classical computers struggle with (pragmaticcoders.com).

In diplomacy, this could mean more accurate forecasting of how different negotiation strategies play out or instantaneous processing of all historical diplomatic data to suggest novel solutions.

Another area is optimization and resource allocation, crucial for peacebuilding. Post-conflict reconstruction or humanitarian relief involves allocating limited resources (food, medicine, peacekeepers) in an optimal way to stabilize societies. Quantum AI algorithms are well-suited for solving optimization problems, so they could help planners find the best distribution of aid that minimizes unrest or the best deployment of peacekeepers to quell violence with minimal force.

Quantum cryptography and secure communication also fall under this umbrella. Quantum technology offers methods like Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) which allow theoretically unbreakable encryption. Ensuring diplomatic communications and negotiation backchannels are secure from eavesdropping is vital for building trust. We can imagine future peace talks secured by quantum encryption, giving negotiators confidence that they can communicate frankly without leaks – a factor that could have been game-changing in historical negotiations where secrecy was paramount.

However, Quantum AI also brings serious risks that could destabilize the current order if not managed. A foremost concern is that a powerful quantum computer could break most existing encryption algorithms (which protect everything from military communications to financial transactions). In effect, “quantum AI systems could breach the strongest defenses and rewrite the rules of digital security overnight”. If, for example, one nation achieved a quantum AI breakthrough secretly, it might decrypt its rivals’ confidential communications, potentially uncovering secrets or bluffing strategies in negotiations. This asymmetric advantage could tempt pre-emptive actions or trigger a security dilemma – other states reacting out of fear of what the quantum-enabled state might do. The mere prospect has already led to urgent calls for developing post-quantum cryptography to replace current encryption before a cryptographically relevant quantum computer emerges.

Additionally, the integration of AI with quantum computing could supercharge cyber warfare. An AI that controls cyber offensive tools, running on a quantum computer, might penetrate systems that were previously secure. Imagine an AI rapidly disabling another nation’s early-warning radar or power grid – the balance of power could shift in seconds, undermining strategic stability. The UN Security Council has cautioned that the fate of humanity should “never be left to the black box of an algorithm” and emphasized that humans must always retain control (blog.biocomm.ai).

This warning resonates even more strongly when considering AI operating at quantum speed and complexity – the potential for loss of human control, accidental escalation, or even AI misjudgments could be amplified.

In terms of global stability, quantum AI is a double-edged sword: it can be a force multiplier for both peace and war. It could empower international institutions to solve problems that are currently intractable (like precisely predicting the impacts of climate-security linkages or designing incentive structures that keep rogue states engaged in treaties). At the same time, if weaponized or applied without international oversight, it could accelerate arms races – not just in nuclear or conventional arms, but in AI and computing superiority. We might see a scramble where states pour resources into quantum AI to avoid falling behind, similar to the nuclear arms race but in the digital realm.

To harness the upside and mitigate the downside, diplomatic efforts around Quantum AI (“quantum diplomacy”) are beginning. Experts suggest we may eventually need international treaties to control the proliferation of advanced AI and quantum technologies, akin to nuclear arms control treaties (cgai.ca). This could include agreements not to use quantum AI for offensive cyber attacks on critical infrastructure, or agreements to share quantum breakthroughs for peaceful purposes (like climate modeling) while banning their use in autonomous weapons. The Canadian Global Affairs Institute in 2017 noted that the convergence of AI, robotics, and quantum computing will demand “an entirely new set of diplomatic initiatives” much like those that monitored and controlled nuclear weapons).

Moreover, ensuring equitable access to AI and quantum computing will be important so that smaller states and developing countries aren’t left behind (harkening back to the UN’s point that AI should not stand for “Advancing Inequality” (press.un.org). Otherwise, quantum AI could widen the gap between tech-superpowers and the rest, creating tensions and grievances in the international system.

In summary, Quantum AI holds great promise for enhancing global stability – from better conflict prediction to unhackable communications – but it must be approached with caution. The international community is aware that without proper guardrails, this technology “could rewrite the rules of digital security overnight”, potentially destabilizing peace. Through proactive governance, transparency, and possibly new arms control regimes focused on emerging tech, we can strive to ensure quantum AI augments our capacity to keep peace rather than undermining it.

Historical Perspectives and Case Studies

Examining past peace processes through the lens of “what if AI existed then” yields insights into how current and future technologies might help resolve conflicts faster. Here we consider a few historical cases and how AI tools could have altered their trajectories, as well as instances in recent history where AI did play a role in de-escalation.

- Northern Ireland – The Good Friday Agreement (1998): This landmark peace agreement ended decades of sectarian conflict known as “The Troubles.” Negotiators spent two years in multi-party talks hammering out the terms (ireland.ie), and even then, implementation took years and required sensitive handling of communal tensions. Had modern AI been available, it might have accelerated consensus-building. For example, AI analytics could have parsed through decades of conflict incident data to identify the core grievances driving violence and suggest targeted confidence-building measures (like reforms in policing or justice) that would most significantly reduce violence. During talks, an AI assistant could have helped Senator George Mitchell (the chief mediator) by continually analyzing the parties’ proposals against public opinion in Northern Ireland – perhaps via sentiment analysis of local media or town hall transcripts – to ensure any draft agreement addressed the public’s primary concerns. If misinformation or hardline propaganda threatened to derail the peace (as almost happened with paramilitary splinter groups spreading rumors), AI-driven monitoring could have alerted authorities to intervene with factual communications. In short, AI’s ability to organize information and forecast reactions might have streamlined the negotiation of the Good Friday Agreement, or at least helped avoid some of the last-minute crises that nearly derailed it. While the agreement was ultimately successful, one can speculate that AI tools might have gotten the parties to “Yes” a bit sooner by revealing hidden common ground (for instance, identifying that both communities valued local self-governance, leading to the idea of devolved power-sharing).

- Israel-Palestine Peace Negotiations: Efforts to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict (Oslo Accords in the 1990s, Camp David 2000, etc.) have thus far fallen short of a final peace. This longstanding conflict is characterized by deep mistrust, complex issues (borders, refugees, security, Jerusalem), and frequent breakdowns in dialogue. AI could contribute in several hypothetical ways. Negotiation Simulation might allow mediators to test various deal frameworks (two-state configurations, confederation models, resource-sharing schemes) in a virtual environment to see which might have the best outcomes for both peoples. By modeling the trade-offs of different proposals – for example, an AI could evaluate how a particular border drawn through Jerusalem impacts security incidents, economic access, and population satisfaction over time – negotiators could refine proposals that maximize mutual benefit. Additionally, AI translation and cultural analysis tools would be valuable in bridging narratives; often Israelis and Palestinians talk past each other due to differing historical lenses. AI trained on both Hebrew and Arabic discourse could help rephrase messages in a way that is more acceptable to the other side, reducing misunderstanding (defenceagenda.com). In terms of on-the-ground impact, one real contribution of AI today is in monitoring flashpoints: for instance, AI vision systems analyzing CCTV in Jerusalem or the West Bank could give early warning of escalating clashes (like noticing crowd formations or incendiary graffiti appearing), enabling security forces or peacekeepers to intervene non-violently. While these applications cannot solve political disagreements by themselves, they could mitigate factors that lead to breakdowns – such as miscommunication and surges of violence – thereby keeping negotiations on track longer.

- Cold War Diplomacy and Arms Control: The Cold War (1947-1991) saw numerous close calls (the Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962; the Able Archer NATO exercise scare, 1983) and hard-fought diplomatic achievements (arms control treaties like SALT I/II, INF). AI was in its infancy then, but even so, as noted earlier, basic machine learning was experimented with to predict the U.S.-Soviet arms race (weizenbaum-institut.de). If we imagine today’s AI in that era, certain crises might have been handled differently. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, for example, President Kennedy and Premier Khrushchev had very limited information and time. A modern AI early-warning system might have detected the Soviet missile deployments in Cuba earlier (via satellite image analysis) and perhaps even forecast that a naval blockade would likely avoid war better than an airstrike (by simulating conflict escalation paths). Moreover, a decision-support AI could have synthesized vast intelligence reports, avoiding the famous miscommunications and advising calmer responses. On the arms control front, one reason treaties like SALT took so long is that verifying compliance was difficult – national technical means were just developing. If AI satellite-analysis and anomaly detection had been available, each side might have trusted verification enough to agree to deeper cuts sooner, knowing cheating would be caught. Conversely, one must acknowledge a cautionary tale from this era: in 1983, the Soviet early-warning system falsely signaled an incoming U.S. missile attack, and only human judgment prevented a catastrophic response. A poorly designed AI might have made the wrong call and launched a retaliation. This underscores that human oversight over AI in military decisions is crucial, a lesson that still guides us (as emphasized by the UN: “AI without human oversight would leave the world blind” (press.un.org). Overall, AI’s presence in the Cold War could have been double-edged – possibly hastening détente through better communication and verification, but also introducing new risks if misused. The key lesson for today is that integrating AI into security policy must be accompanied by strong safeguards to prevent technical glitches from becoming worldly disasters.

- Recent Examples of AI Aiding Peace: While comprehensive historical uses of AI in preventing wars are still few (since the technology is so new), there are growing instances where AI has tangibly helped de-escalate tensions. In several conflict-prone countries, AI-based social media monitoring has allowed early intervention. For example, in Kenya, tech firms and civil society used AI tools to monitor hate speech online around the 2013 and 2017 elections, helping authorities and platforms remove dangerous content and send peace messaging, which many analysts believe contributed to calmer outcomes compared to the violence in 2007. Another emerging example is the use of predictive policing algorithms in UN peacekeeping missions – not for law enforcement per se, but to anticipate where violence might break out. If a UN mission knows through data analysis that certain villages are at high risk of interethnic clashes this week (perhaps due to a local provocation circulating on WhatsApp), they can increase patrols or facilitate dialogue in those villages, thereby preventing an incident. AI-driven early warning systems have indeed been credited with informing such preventative deployments (kluzprize.org). The ViEWS project mentioned earlier is one such tool: while an academic project, its conflict forecasts are publicly available and can guide NGOs or governments to direct resources to areas of rising risk (kluzprize.org). There’s also the example of UN Global Pulse’s radio analysis in Uganda (thesecuritydistillery.org) – by identifying local grievances before they turned into unrest, it gave peacebuilding teams a chance to address issues through community meetings, effectively defusing what could have become a flashpoint. These cases hint at AI’s real potential: even if it’s behind the scenes, AI is starting to quietly inform decision-makers in ways that alter the course of events toward peace. Each prevented clash or diffused standoff, even if small, adds up in the grand scheme of conflict prevention. As AI tools become more widespread, we may see more overt examples – such as an AI identified rumor that was quashed and thereby prevented a riot, or an AI forecast that led two rival nations to open diplomatic talks just in time to avert war. The goal moving forward is to learn from these early uses and scale up AI’s positive impact on peace.

AI Applications in Peacekeeping Operations

Modern peacekeeping missions — such as United Nations deployments to conflict zones — are embracing technology to better protect civilians and maintain ceasefires. AI can be integrated into these missions at multiple levels to enhance effectiveness while minimizing risks to peacekeepers. Here we outline several key applications of AI in peacekeeping and international security frameworks:

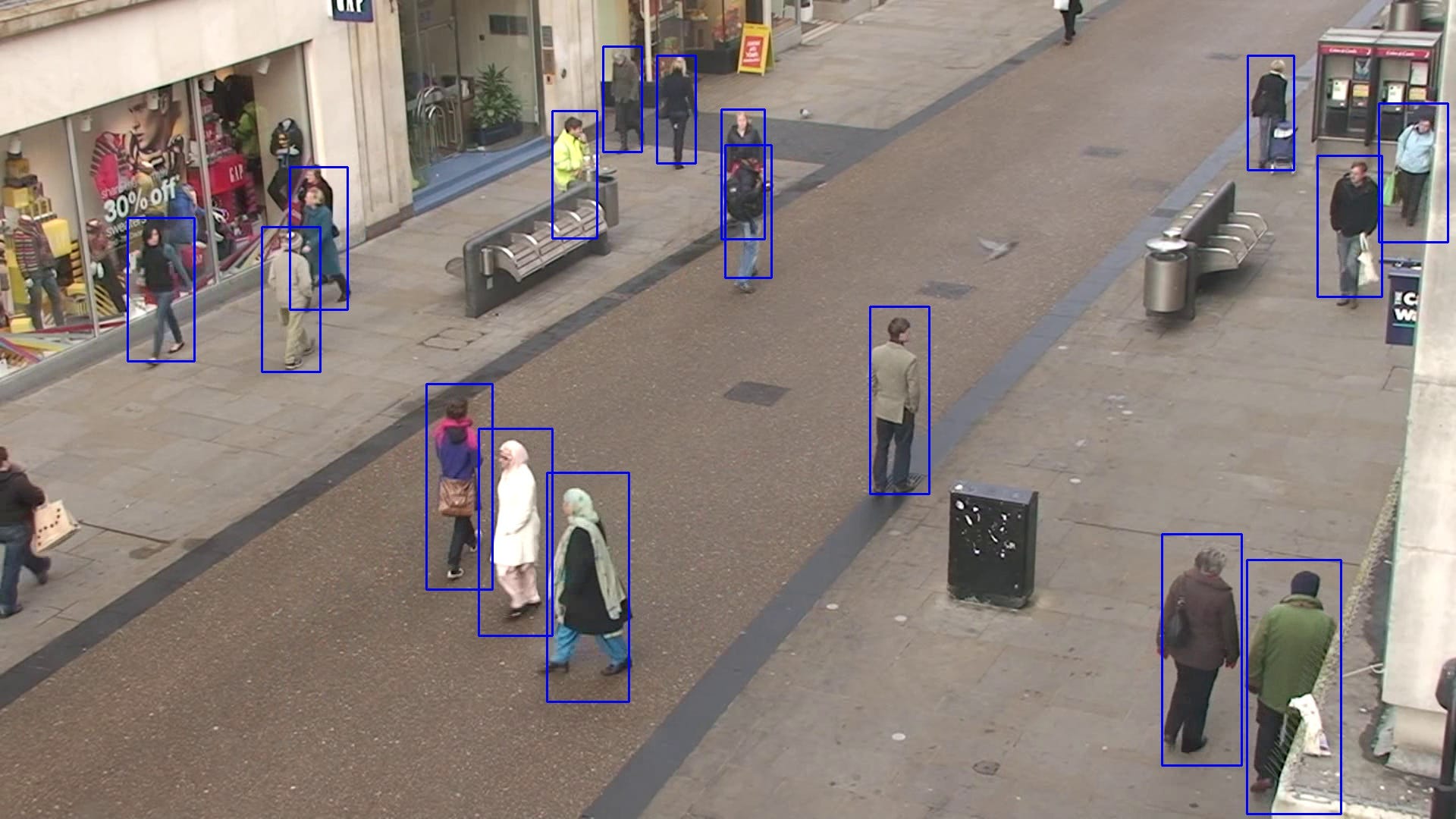

- Surveillance and Situational Awareness: Peacekeepers often operate in vast areas with limited personnel. AI can act as a force multiplier by providing 24/7 surveillance and instant analysis. Drones equipped with AI vision algorithms can patrol conflict lines autonomously, as mentioned earlier, to monitor ceasefire compliance (pragmaticcoders.com). These drones relay live video, which AI software analyzes to detect troop movements, gunfire flashes at night, or the buildup of weapons. Similarly, AI-enhanced satellite surveillance can keep an eye on remote regions where peacekeepers can’t always be present. By improving situational awareness, AI helps mission commanders allocate their troops optimally and react to incidents faster. For instance, if an AI system monitoring a buffer zone detects armed individuals crossing (a potential ceasefire breach), it can immediately alert the mission control, which can dispatch a patrol or contact the conflict parties to address it before it escalates.

- Autonomous Non-Lethal Systems: While the deployment of lethal autonomous weapons in peacekeeping is controversial and generally avoided, autonomous non-lethal systems are more acceptable and increasingly feasible. Unarmed ground robots or drones could perform hazardous tasks like route clearance (looking for IEDs or mines) or standing guard at observation posts, thus keeping human peacekeepers out of harm’s way. AI-powered robots might also be used for crowd control and protection in a non-violent manner – for example, drones that can disperse rioting crowds by broadcasting loud messages or shining lights, without using force. Though such use is experimental, it could reduce casualties. The key is that AI allows these systems to operate with minimal human input: a single operator could oversee a fleet of security robots that navigate and respond on their own, intervening only when necessary. An illustration of this concept is the idea of unarmed AI observers in a conflict – essentially impartial robotic “blue helmets” that can position themselves between hostile factions to provide a buffer and record any aggression. This is a futuristic notion, but technically within reach as AI navigation and object recognition improve.

- Logistics and Operational Support: Peacekeeping missions face massive logistical challenges, from moving troops and supplies to evacuating wounded civilians. AI optimization algorithms can greatly assist here. They can plan supply routes that minimize risk and cost, forecast consumption of fuel/food/medicine based on troop movements and local needs, and dynamically re-route convoys if intelligence (perhaps AI-analyzed) indicates a threat on the planned path. By increasing efficiency, AI-driven logistics mean missions can do more with limited resources (thesecuritydistillery.org). This might even encourage more countries to contribute to missions, knowing their contributions will be used optimally (thesecuritydistillery.org). Additionally, AI-based maintenance systems predict when vehicles or equipment will fail and need repair (predictive maintenance), reducing downtime and mission disruptions. In hostile terrains, autonomous cargo drones could resupply remote outposts without risking manned convoys – guided by AI to land precisely even in rough conditions.

- Training and Simulation: Preparing peacekeepers for complex conflict environments is critical. AI-enabled training simulations can create realistic scenarios (riots, ambushes, negotiations with local leaders, etc.) to train peacekeeping troops and commanders. Virtual reality environments, combined with AI-driven characters (civilians, militia, etc.), allow peacekeepers to practice responses to various situations in a safe setting (thesecuritydistillery.org). For example, an AI simulation could train a unit on how to de-escalate a standoff at a checkpoint by simulating different behaviors from local civilians and armed groups, learning what tactics work best. Some contributing countries with less training infrastructure could benefit from these virtual trainers shared by the UN, leveling up troop preparedness (thesecuritydistillery.org). By the time they deploy, soldiers would have encountered many scenarios virtually, leading to more effective and restrained responses on the ground.

- Decision Support and Knowledge Management: In the field, peacekeepers must make quick decisions often with incomplete information. AI can help integrate multiple information streams – patrol reports, intelligence, open-source media, etc. – into a coherent picture. For instance, the mission HQ might use an AI system that takes daily reports from different sectors and highlights emerging trends: “Sector A is seeing increasing protests, Sector B had two ceasefire violations this week, and social media sentiment in Sector C is worsening.” This kind of dashboard, powered by AI analytics, enables commanders to prioritize areas and anticipate needs. Moreover, AI chatbots can serve as digital assistants for peacekeepers, answering queries like “When was the last clash in this village?” or “What are the local conflict dynamics and key community leaders here?” by instantly retrieving info from databases. Some missions are experimenting with natural language interfaces that let personnel access the collective knowledge of the mission (including past mission data) without having to manually sift reports.

- Local Engagement and Cultural Sensitivity: Understanding local context is paramount in peacekeeping. AI tools like automatic translators help peacekeepers communicate with local populations in their native languages on the fly (thesecuritydistillery.org). This builds trust and avoids miscommunication. Sentiment analysis of local radio, social media, and news (as previously noted) gives peacekeepers a read on the community’s mood (thesecuritydistillery.org). If the local population is growing frustrated about some issue (say, misconduct by a peacekeeper or a rumor of bias), the mission leadership can proactively address it – perhaps through a community meeting or better public information – before it undermines the mission. Essentially, AI can function as an interface between the peacekeeping operation and the society it serves, ensuring the mission stays responsive and respectful to those on the ground.

- Integration into International Frameworks: At a higher level, AI is being integrated into the planning and coordination among international security bodies. The United Nations has recognized the need to leverage AI for peacekeeping; for example, UN Policy Briefs on a New Agenda for Peace call for innovative tech use in conflict prevention (unitar.org). The UN’s Department of Peace Operations and the Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs have set up expert teams and even a Centre for Artificial Intelligence and Robotics (under UNICRI) to research AI applications for peace (thesecuritydistillery.org)

In NATO and regional organizations, discussions are underway about standardizing AI tools for shared situational awareness in multinational operations. We are likely to see more formal programs like “Digital Peacekeepers” or joint AI-driven early warning centers in the near future.

While these applications offer significant advantages, implementing AI in peacekeeping also requires careful management of expectations and risks (which we address in the next section). The hardware and software must be secure against hacking (imagine an AI surveillance drone being taken over by a hostile force – a nightmare scenario). Peacekeepers must also be trained to work with AI outputs and not become overly reliant or complacent. Nonetheless, the trajectory is clear: AI is becoming an integral part of peacekeeping. It augments human peacekeepers – who will always be essential for the empathy, judgment, and legitimacy they provide – by handling information overload, performing dull or dangerous tasks, and providing analytical clarity. In a sense, AI allows peacekeepers to “keep the peace” more intelligently and safely, from the planning of a mission to the execution on the ground.

Ethical and Strategic Implications

The incorporation of AI (and especially Quantum AI) into warfare, diplomacy, and peacekeeping raises profound ethical and strategic questions. Ensuring that these technologies bolster peace rather than undermine it requires grappling with challenges of bias, transparency, control, and reliance. Here, we outline some of the most pressing implications:

- Algorithmic Bias and Fairness: AI systems are created by humans and trained on historical data, so they can inadvertently inherit biases. In a diplomatic or peacekeeping context, this is dangerous. A conflict prediction AI might weigh data in a way that unfairly stigmatizes a particular ethnic group or region (perhaps because historical data showed more violence there, without context as to why). If policymakers unknowingly trust such a biased model, they could allocate resources unjustly or, worse, treat one side of a conflict with undue suspicion. Similarly, an AI translation tool might miss cultural nuances or use phrasing that offends one party. It’s crucial to ensure AI used in peace and security is inclusive and tested for bias. This means involving local stakeholders in AI development, using diverse training data, and continuously auditing outputs. As expert Martin Wählisch noted, “cultural biases embedded in algorithms and the widening digital divide remain significant challenges” in using AI for peace (weizenbaum-institut.de). If those biases aren’t addressed, AI could exacerbate inequalities or inflame tensions – the opposite of its intended role.

- Transparency and Trust: AI’s “black box” problem – the difficulty of understanding how complex algorithms make decisions – can be problematic in high-stakes international affairs. Diplomats or military leaders might be presented with an AI recommendation (e.g. that a certain city is at risk of violence next month) without a clear explanation. Acting on such opaque advice can be hard to justify, especially if actions fail. Conversely, ignoring AI warnings because they are not understood could mean missing real threats. Transparency is thus essential. Wherever possible, AI tools should provide interpretable reasons (“Indicator X and Y are spiking, similar to patterns before past conflicts”) to support their conclusions. Moreover, there’s the issue of transparency between nations: if one side in a negotiation is using AI analysis, should it disclose this to the other to maintain trust? Perhaps international norms will emerge that any AI-informed assessments that influence negotiations or UN Security Council decisions should be shared or vetted multilaterally. This ties into the concept of explainable AI – making AI’s actions explainable to human overseers is critical to building confidence in their use. Without transparency, diplomats may dismiss AI inputs, or worse, misinterpret them. As a caution, the UN Secretary-General has stressed that humanity’s fate must not be left to mysterious algorithms, and that human control and understanding are non-negotiable (blog.biocomm.ai).

- Overreliance and Human Judgment: While AI can greatly aid decision-making, there’s a concern that leaders might become over-reliant on algorithmic predictions or suggestions, potentially eroding human judgment and responsibility. Military officers might start deferring to “what the computer says” for threat assessments; negotiators might lean too heavily on an AI’s proposal and fail to exercise creativity or empathy. Over-reliance is dangerous because AI, no matter how advanced, can be wrong – and in peace and war, wrong decisions cost lives. A sobering thought is what happens if an AI predicts war is inevitable in a region; could that become a self-fulfilling prophecy as parties gear up for conflict, trusting the AI more than late-breaking diplomatic opportunities? One analysis warns that autonomous systems should not erode critical human judgment in high-stakes scenarios, and balancing human oversight with AI efficiency is crucial (defenceagenda.com). Humans must remain in the loop, ready to question or override AI recommendations based on context, values, and intuition. Maintaining this balance may require training a new generation of “AI-literate” diplomats and soldiers who know the strengths and limits of these tools. Strategically, it also means always having a Plan B – if the AI systems go down or prove unreliable (say, due to a cyberattack or a sudden change the model didn’t anticipate), humans need to be able to take charge seamlessly.

- Misuse and Malicious Use: Any tool can be misused, and AI is no exception. We’ve discussed misinformation as a malicious use of AI. But consider other scenarios: An authoritarian regime might use AI to feign engagement in peace talks while actually stalling – for instance, using deepfakes of supposed rebel statements to confuse international mediators. AI could be used to micro-target propaganda to derail peace processes (imagine tailored messages to different groups to turn them against an agreement). Even in negotiation, there’s a concern one side could use AI to gain advantage in an unethical way, such as analyzing the other negotiator’s personal data to find psychological pressure points – effectively weaponizing information to coerce rather than compromise. On the military side, autonomous weapons or surveillance AI could be deployed under the banner of peacekeeping but then repurposed for aggression (a robot meant to protect civilians could be reprogrammed to attack opposing forces autonomously, violating agreements). The international community is aware of these risks; hence efforts like the Political Declaration on Responsible Military Use of AI (launched by the US and others) which aims to set norms so AI is not misused in ways that undermine peace (state.gov). Ensuring accountability is key: if an AI does cause harm (say a faulty facial recognition wrongly targets a civilian as a combatant), clear lines of accountability and redress must exist. Without them, trust in AI among populations would erode, fueling resentment.

- Reliance on AI Predictions in Diplomacy: As AI predictions get more sophisticated, diplomats might face a new kind of dilemma. If an AI consistently predicts that a certain country will violate a treaty or that a peace deal will fail, it might color the perceptions going in. This raises a worry about self-fulfilling prophecies or fatalism – leaders might not put full effort into peace if “the AI says it’s hopeless.” Alternatively, if AI gives an all-clear, leaders might let their guard down imprudently. There’s also a psychological aspect: parties to a conflict might mistrust a peace proposal if they know it was partially drafted by AI, fearing it’s a ploy or too abstract. They might say “we want a human negotiator who understands our plight, not a computer output.” Ethically, negotiators should use AI as a behind-the-scenes aid, not a replacement for genuine human engagement. The credibility of peace efforts could be at stake if one side suspects the other is delegating empathy and compromise to a machine. To mitigate this, transparency (again) and a human-centered approach to AI in diplomacy are needed. AI can present options, but humans must take ownership of the choices made.

- Security and Errors: From a strategic stability perspective, heavy reliance on AI carries risks of technical failure or adversarial manipulation. If a conflict prediction AI that many nations rely on (imagine a future UN-run system) has a bug or is hacked to give false alarms, it could trigger unnecessary military mobilizations. Likewise, an AI arms control monitor that falsely reports a treaty violation could collapse an agreement unless double-checked. We must plan for fail-safes and independent verification of AI outputs. This might involve having multiple AI models from different sources (“AI second opinions”) or maintaining traditional intelligence methods as a cross-check. In nuclear command and control, experts vehemently advise against fully autonomous decision-making because the cost of a mistake is too high – this principle likely extends to any scenario of war and peace. AI should inform human decision-makers, not replace them, especially where the margin for error is zero.

In light of these concerns, ongoing efforts seek to create an ethical and governance framework around AI in international peace and security. For instance, the UN’s High-Level Advisory Body on AI is working on a global framework that addresses both risks and opportunities of AI (press.un.org). They advocate for things like an International AI Observatory or Panel to monitor developments and advise on risk reduction. Many experts call for common standards of AI safety, testing, and validation – analogous to how aircraft or nuclear plants are subject to rigorous checks – before deploying AI in conflict-sensitive roles. The concept of “human-in-the-loop” decision systems is gaining traction as a norm: that critical decisions (like use of force) must get human sign-off, no matter what the machine recommends.

Finally, one strategic implication to note: AI could shift power dynamics. Countries or groups that harness AI effectively could gain significant leverage in negotiations or military standoffs. This raises questions of AI equity – making sure poorer nations also benefit from AI for peace (as Guterres noted, not letting AI drive inequality). Otherwise, only wealthy nations would have the top predictive tools or autonomous peacekeepers, potentially sidelining others in international forums. Democratizing access to AI for conflict resolution (through UN support or open-source tools) may become an important policy goal to ensure a balanced and fair international system.

In summary, the march of AI into warfare and peacekeeping is inevitable, but it must be guided by ethical considerations and strategic prudence. Bias must be checked; transparency and human oversight must be built-in; misuse must be guarded against by international law; and humans must remain morally and practically accountable for peace and war decisions. By anticipating these challenges now, we increase the odds that AI will serve as a catalyst for global stability rather than a source of new conflict. After all, as one analysis put it, while militarization of AI poses risks, if we prioritize ethical development and cooperative applications, “AI can become a cornerstone of global stability.”(defenceagenda.com).

Global Initiatives and Research Advancing “AI for Peace”

Recognizing both the potential and the perils of AI in international security, a range of initiatives have emerged from governments, international organizations, and NGOs to harness AI for peacekeeping and conflict resolution:

- United Nations and Multilateral Efforts: The UN is at the forefront of shaping a global approach. In July 2023, the UN Security Council held its first ever session on AI’s implications for peace and security (press.un.org). Secretary-General Guterres has proposed establishing an International Scientific Panel on AI and a Global Dialogue on AI Governance as part of a broader Global Digital Compact (press.un.org).

These would bring together experts and member states to set guardrails and share best practices. Within the UN system, bodies like UN Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (DPPA) have innovation teams exploring data analytics for conflict prevention (as evidenced by Martin Wählisch’s work on AI in mediation within the UN) (weizenbaum-institut.de).

The UN Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR) has been examining AI’s risk of miscalculation, escalation, and proliferation in military contexts and how to mitigate them (cambridge.org). Another UN entity, the Centre for AI and Robotics (UNICRI), based in The Hague, focuses on how AI can be used in crime prevention, terrorism prevention, and peacekeeping, ensuring these technologies are applied responsibly (thesecuritydistillery.org). In 2024, UNIDIR’s Innovations Dialogue specifically looked at transformative tech including quantum, AI, and blockchain in security (unidir.org), highlighting cross-cutting expertise. All these point to a concerted push within the UN to not only use AI operationally but also to convene member states around norms – much like earlier efforts on nuclear non-proliferation or cyber security.

- Government Initiatives: Individual governments or coalitions are also proactively addressing AI in security. In February 2023, more than 60 nations endorsed the Political Declaration on Responsible Military Use of AI and Autonomy, pledging to ensure human accountability, avoid bias, and share best practices in military AI (state.gov). This is a soft-law instrument, but it’s a start towards international norms. Some governments have set up dedicated units – for example, the U.S. State Department’s International Security Advisory Board (ISAB) released a report on AI and associated technologies, discussing arms control verification and global stability implications. NATO has an AI strategy (adopted in 2021) emphasizing principles of lawfulness and responsibility for any AI used by Allied militaries. The European Union, apart from its AI Act regulating AI broadly, funds peace-specific AI research: projects under Horizon Europe looking at early warning systems, disinformation countermeasures, etc., often in collaboration with UN or African Union peace architecture (cambridge.org). China and Russia have been more focused on military AI advantages, but they too participate in discussions at forums like the UN Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) about limits on autonomous weapons. There’s also a developing dialogue between major powers – e.g., U.S. and China have discussed establishing a hotline or norms regarding AI in military to prevent unintended escalation (akin to nuclear hotlines) (itnews.com.au). .

- Academic and Think Tank Research: Universities and think tanks worldwide have launched programs on AI and peace. For instance, Stanford’s Institute for Human-Centered AI has a Peace and Security initiative, and one of its leaders, Fei-Fei Li, spoke at the UN about balancing AI innovation with vigilance

The Centre for the Study of Existential Risk (Cambridge) and the Future of Humanity Institute (Oxford) look at AI from a global catastrophic risk angle, which includes war prevention. The Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) and Uppsala University’s ViEWS project (kluzprize.org) we discussed is a prime example of academic work directly feeding into policy for conflict prediction. The Weizenbaum Institute in Germany hosted fellows exploring AI in mediation (as seen in the interview we cited) (weizenbaum-institut.de).

Think tanks like Carnegie Endowment and CNAS (Center for a New American Security) have produced reports on AI’s impact on strategic stability and arms control (carnegieendowment.org), often recommending ways to integrate AI into verification or proposing confidence-building measures for AI among rival states.

- NGO and Civil Society Initiatives: A notable trend is the rise of the “PeaceTech” movement – NGOs and tech entrepreneurs working together to solve peace and humanitarian problems with technology. The PeaceTech Lab, spun off from US Institute of Peace, has projects that leverage big data and media analytics to counter hate speech and violence in places like South Sudan and Iraq. The Kluz Prize for PeaceTech (by Kluz Ventures) specifically awards innovations in this space; in 2024, their event highlighted AI for conflict prevention and had case studies on early warning and AI-aided humanitarian response (kluzprize.org). This indicates private sector involvement in positive AI uses. Additionally, organizations like the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) are actively researching how AI and autonomy can be reconciled with international humanitarian law – to ensure even in warfare, AI is used in ways that minimize harm to civilians.

- Cross-sector Collaborations: Because effective use of AI for peace often requires combining technical know-how with on-the-ground experience, we see cross-sector partnerships. For example, the NYU Peace Research and Education Program (PREP) brought UN officials, tech companies, and academics together to discuss practical AI applications for good. Hackathons and challenges have been launched inviting young innovators to build AI solutions for peacekeeping problems (like better translation for missions or predictive models for election violence). Even tech giants like Google and Microsoft have grant programs for AI-for-good, some of which include peace and human rights projects (Microsoft’s AI for Good initiative has supported projects mapping atrocities via satellite imagery, etc.).

All these efforts are building a nascent ecosystem focused on “AI for Peace.” The encouraging part is the emphasis on responsible use. Nearly every initiative couples the technological discussion with an ethical one – as seen in the Kluz Prize event where speakers stressed applying AI responsibly to avoid harm (kluzprize.org), or the UN AI for Good conferences that highlight human-centric and transparent AI.

Governance is still catching up, but momentum is there. Experts often cite the need for something akin to the “Sputnik moment” in AI governance – a galvanizing realization among nations that cooperation is needed to manage this powerful technology. Some argue the world is already in an AI arms race; others see more room for cooperative security approaches. One tangible proposal on the table is an international treaty banning fully autonomous weapons (advocated by the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots and many states at the UN CCW talks). While not directly about diplomacy AI, it’s related in that it sets a baseline that life-and-death decisions should stay under human control, which supports global stability. In the realm of diplomacy-assisting AI, we might not need a treaty, but perhaps agreed principles, such as: AI should augment, not replace, human negotiators; all parties in a mediation should have equal access to AI tools to avoid unfair advantage; and data used by AI mediators should be shared and vetted for bias.

Looking ahead, the continued sharing of best practices will be crucial. A positive sign is that many of these initiatives publish their findings openly – for example, PRIO’s ViEWS dashboard is online for anyone to explore (kluzprize.org), and Cambridge’s Data & Policy journal (from which we cited “AI for peace” analysis) disseminates research on this topic freely (cambridge.org). Such transparency helps democratize knowledge.

In conclusion, the world is actively exploring how to steer AI toward peace and away from destruction. It’s a multidisciplinary, international effort, appropriately so given the global impact of these technologies. Through UN leadership, national policies, academic insight, and civil society innovation, a framework is gradually emerging to ensure AI and Quantum AI become tools of diplomacy, understanding, and human security. The task now is to strengthen and implement this framework before the technology outpaces our institutions. The promise of AI in preventing war and sustaining peace is great – and with wise guidance, it can be realized for the benefit of all.